(A Hiatus from Chiasmus, to which I will return)

There is something fitting about silence in Advent. Yes, silence. Quiet. Stillness. Advent is a season of waiting, of looking forward—with eager yet restrained anticipation—to the twenty-fifth night of December, when, the whole world being at peace, Christ was born.

But Advent is often anything but a silent season, and from the confines of our homes to society at large, the world seems anything but at peace. We are accosted by advertisements and Christmas songs, and we are consumed by baking and the making of plans. Life in academia teems with term papers, thesis work, and homeward travels. Between the business of preparation and the busyness of pre-emptive celebration, Advent can, in fact, become quite tiresome… It can become so impressively festive, so incredibly hurried, so mind-numbingly noisy, that by the time Christmas arrives, there is not a song we did not sing, a pastry we did not taste, or a party we did not attend in the great season of waiting. It wears us out.

So what am I talking about with silence? Put simply, it does not fit into how we observe the season at present. If we were to visibly avert our ears from Michael Búble or Laufey’s Christmas albums and reject every act of hospitality involving cookies, we would be doing a disservice both to our witness in the world and to the spirit of the season, which allows us to anticipate the joys of Christmas to a certain degree. But while Advent anticipates Christmas, it also anticipates the second coming; the first few weeks of the lectionary brim with images of the Kingdom and calls to conversion as we anticipate Christ’s return. And as such, we ought to retain a spirit of vigilance and restraint in this time.

I propose that a more balanced approach to the season—one that does not confuse it with Christmas entirely—requires us first to re-evaluate our baseline dispositions. Let me explain.

In my reading of the Philokalia, I stumbled upon this great passage from Ilias the Priest’s Third Gnomic Anthology:

The three most comprehensive virtues of the soul are prayer, silence, and fasting. Thus you should refresh yourself with the contemplation of created realities when you relax from prayer; with conversation about the life of virtue when you relax from silence; and with such food as is permitted when you relax from fasting. So long as the intellect dwells among divine realities, it preserves its likeness to God being filled with goodness and compassion.

Here, he describes well what ought to be our normative state as we await Christ’s second coming: one of prayer, silence, and fasting. While their complements, common contemplation (a prayerful consideration of the created world), virtuous conversation with the other, and temperate food and drink consumption are by no means condemned, they are put into their proper place: as relaxations from prayer, silence, and fasting, and not the opposite.

The enjoyment of Christmas music, conversation, sweets, and holiday drinks has become the norm for observing Advent in the world. While we can enjoy Christmas cheer in the air, seasonal pastries, and the sound of hymns, I fear that their primacy of place in Advent has caused us to hold them in lower esteem when their proper time has actually come about. Few people find Christmas music palatable through Candlemas, let alone Theophany, let alone Epiphany, let alone the Octave, let alone New Year’s Eve…

By cultivating a spirit of quiet, such that we view quiet as our normative state—the place from which and to which all else returns—we shall find ourselves much more eager to hear the sweetness of Advent and Christmas hymns at mass and in coffee shops. When we hold silence as something sacred, we will be able to appreciate music and conversation with a greater reverence, since it is no longer mere background noise. I am encouraged by the fact that, despite the world’s clamor, there are still two words that do not pass our lips in earnest until the twenty-fifth day of December. We keep that sacred greeting silent until Christ is born on Christmas day. I am hopeful that such a thing can be regained gradually by all Christians with regard to Christmas music, such that it once again becomes something more sacred than commonplace.

And likewise by reframing fasting as our normative state in Advent, such that we consider each meal—or each reception of someone else’s kindness in the form of pastries—as a relaxation from our little fasts, we shall find ourselves looking forward with greater fervor to feasting with friends and family in Christmastide. While in our Church the role and rule of fasting has been vastly diminished, we should consider that Eastern and Coptic Orthodox Christians eat only vegetables during this time of preparation.

A chief point we can take from Ilias’s text is this: when we view prayer, silence, and fasting as deviations from our normal way of living, our gaze is revealed to be more consistently on things of this world than of heaven, and our lives easily become overrun by noise and stimulation of the senses. But when we make prayer, silence, and fasting our normal way of living, then we become more mindful of our daily tasks, the sound that enters our ears, the food that enters our bodies, and the way the Lord works through all these things. While the extent to which we reform our approach to Advent is a matter of personal discernment, I think it is nonetheless necessary if we want to celebrate Christmas well. And in reframing our mindsets and reforming our lives around these three things during this time of preparation, we will find ourselves having made greater space for God, whose voice is heard much more easily in the quiet than in the noise.

Advent is perhaps the most fitting time to begin these reconsiderations. The weather is getting colder, the mornings get light later, and the evening is becomes dark earlier. There’s great occasion for stillness right now.

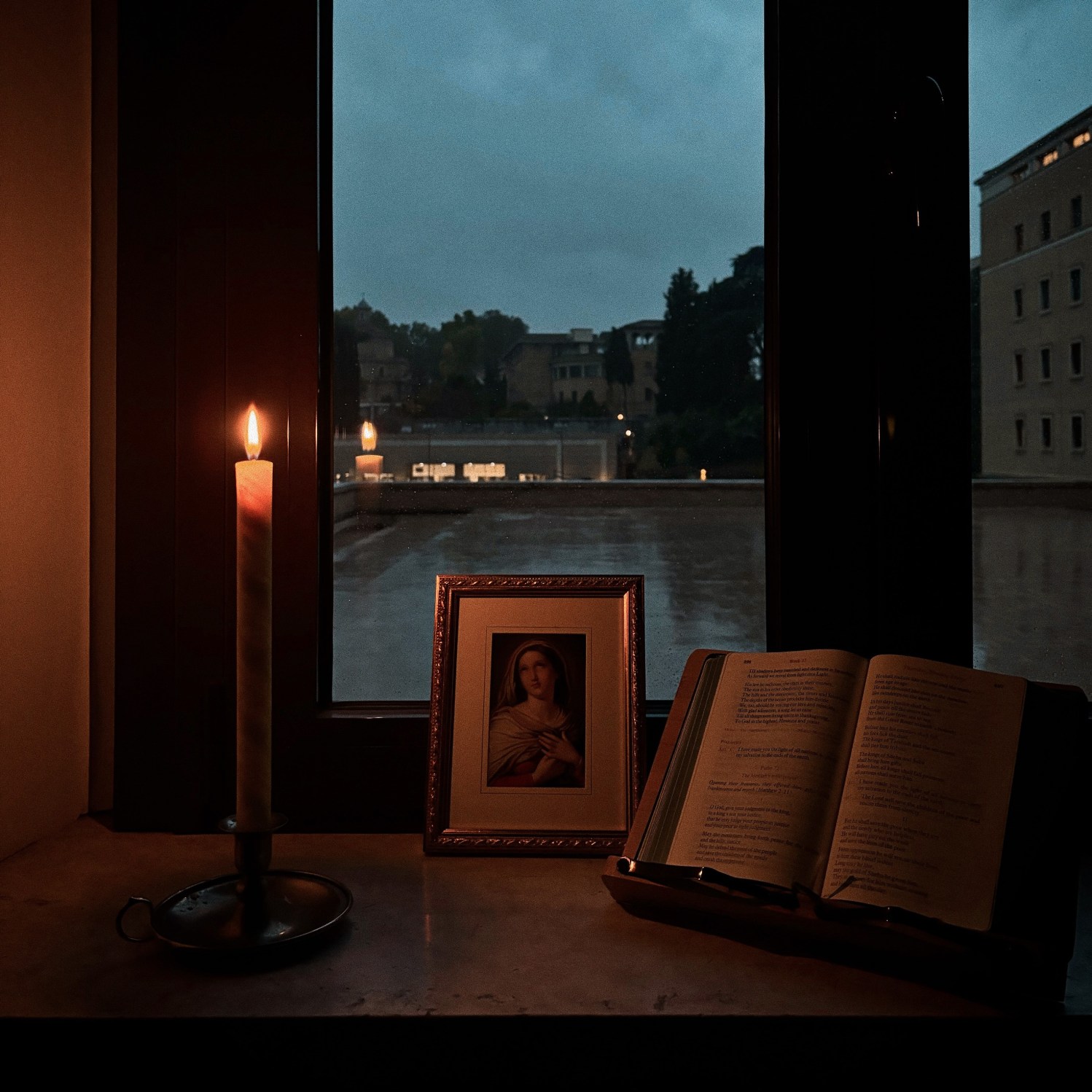

View from my window.